Montréal, 19 August 2015

The current rate of about 1.30 C$/US$ looks a bit stretched compared to recent years. It hovered around parity for a couple of years following the financial crisis and it delightfully sounded as a new normal. As a proper matter of fact the parity has been only a rarity for the past 40 years. For those wondering where the C$ is now heading, remember that the C$ touched a low of 1.62 last 2003. It may seem far in time, but it provides a reality check on poor speculation. If you look at chart 1 displaying the C$/US$ chart over 30 years, you will see that we have roughly completed a 20-year cycle. From 1992 to 2003 the C$ steadily devalued to the point that foreign media were tagging the C$ as the northern Peso. It then steadily strengthened from 2003 to 2009, and remained relatively stable until 2013. In 2013 the C$ turned around anew along with the drop in commodity prices, losing ground and parity, thereby marking the end of a cycle. So here we go again! Once more we need a weakening C$ to get out of a hole. It pays a good deal to examine the last 20 years to see how well we managed our economy and how we should tackle the new growth challenges.

Chart 1 C$/US$ from 1985-2015

Under the Liberals

When Paul Martin, the first architect of the economic recovery achieved under the Liberals, became finance minister in 1994, the situation did not look altogether bleak, but it did look precarious. The country had just come through the 1991 recession and debt had reached C$ 578 billion, or 55% of GDP. To add to the turmoil, the PQ soon got elected in 1994, and jumped straight into crafting their 1995 referendum strategy.

Luckily for the Liberals the NAFTA treaty had just been signed in 1993. The table was set for manoeuvring a steady devaluation of the currency which in turn boosted our export performance to the US for about a decade. With the economy turning around and the Liberals applying austerity in the national books, the country finances finally turned around as well. This extraordinary performance was then overshadowed by the sponsorship scandal amidst an acrimonious leadership transition between Jean Chretien and Paul Martin. It just turned out that this vicious worm had long been digging and furrowing into the Liberal apple. The period of 2002-2005 was thus clouded by an awkward change of political power to the Conservatives. With the politicial focus entangled in national politics, the country somehow misjudged both the rise of China as a manufacturing power and the momentum that would give birth to the super commodity cycle. Canadian manufacturers, drunk on the elixir of a weak C$, woke up to a monstrous challenge: a rising C$ and a tsunami of Chinese competition.

Under the Conservatives

When the Conservatives from Alberta regained power in 2006, they delighted to a dream come through: The odds-on to become an oil super power with no interference from the East, meaning Ottawa. Eventually the commodity boom and the oil sands came to bankroll the economies of Eastern Canada, notably those of Ontario and Quebec, severely hit by China and the financial crisis of 2008. Luckily in turn for the Conservatives the banking system and the country finances had been put to good shape by the Liberals. When the financial crisis hit, the banking system stood firm and the federal government threw in a stimulus package to keep the economy afloat. The C$ devaluation in 2009 turned out to be just a blip on the chart, albeit a significant one, mirroring the oil price movements. So from 2008 to 2013 the C$ held up on the whole rather well, within a comfortable range of C$/US$ 1.00-1.10. The Canadian economy plodded along, with the help of a consumption debt pushing new highs nearly every quarter.

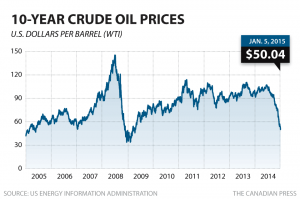

Unusually low interest rates have breathed oxygen to the world economy since 2008, but 7 years later there is a nagging feeling this strategy has run its course. Few countries have taken the breather to properly reform their economic and social structures: On the whole Europe is still wobbling in the ruts of their own ‘lost decade’, whereas BRIC nations have lost their shining attraction. As a result, world economic growth is now slumping to 2.8% for 2015 (below the critical benchmark of 3%, and much dependant on just 3 nations: USA, India and China). This is a fragile context for the rest of the world and the oil market has reacted violently (chart 2). Oil prices took a drop of 50% in less than 6 months! Manufacturing and exporting nations are mildly rejoicing, but commodity nations are licking their wounds. Not surprisingly the C$ has tumbled as rapidly as the oil price.

Chart 2. Oil prices 2005-2015

Now what’s the outlook for the C$?

This will essentially depend on 3 things regarding our economy and how it will grow:

– whether the manufacturing part of our economy can pick up steam

– how long the commodity slump will last

– whether we can take our share of the future high tech and digital economy.

There is a general sense that the Canadian economy has eroded in the last 20 years. Traditional sectors such as fisheries and forestry have taken a beating. Aluminium is now being upended by the same global forces and the outlook remains cloudy from extraction to transformation. Low tech manufacturing such as textiles and apparels have long departed. The car industry in Ontario was weakened by the last financial crisis and finds itself in a declining trend as Mexico is increasingly capturing new automobile factory investments. In telecoms, the rise and fall of two giants, Nortel and RIM, has hit the sector and we lost two very capable R&D franchises. In Montreal, the pharmaceutical industry shrunk by 40% and shifted significant R&D facilities to emerging nations. The last commodity boom has thus conveniently plastered over a loss of competitiveness in several key industrial sectors. Without the oil contribution, the health of many industries would be looking visibly shaky.

Canadian manufacturing did not prepare well during the boom years (1994-2004) to take on the competitive challenge from China. Dutch disease or not, manufacturing lost an estimated 500 000 jobs during the years of a strong C$. And just as manufacturing was coming to see eye-to-eye with China, the financial crisis hit in 2008. No wonder manufacturing cannot rebound today as formidably as politicians would now hope so, despite a lower C$. After 10 years of manufacturing struggles, and given at last a respite in the currency field, where can/should we expect economic growth to come from in the next 10 years?

- Not really from the consumer. Household debt and high real estate prices have now reached levels that could reasonably pose a fair threat to financial stability. The Canadian consumer has not deleveraged since the financial crisis of 2008. He has rather stacked up debt.

- From new government packages? Unlikely. The federal government has kept control of the national debt and has now topped it at 52% of GDP and is aiming at balancing the budget within the next 2 years. Rather, it is provincial governments that are struggling to put a lid on their deficits as they face fierce opposition to austerity measures. Still there is little consensus to lift debt to higher levels.

- Can exports take up the slack? Just possibly. Manufacturing will eventually respond positively to the falling C$ but with a lag and probably less verve: fixed investments have been flat for the last 5 years. We still hear more about closing factories than new investments. Southern American states, Mexico and Asia provide very tough competitive fields to Canada in attracting FDI. Successful high value manufacturing products increasingly require a combination of competitive cost structure, tech performance, design quality and service. This is a combination that Canada has not easily achieved in the past.

- The trade balance has averaged – C$ 6.8 B in the last 5 years and we are on track for much of the same this year. This will be a critical indicator to watch. The US economy should pull us along, but we have lost ground to China and other nations in the US market.

- Will the commodity slump be short lived? Don’t bet on it. It is hard to predict how long will the slump in commodities last. Oil might move faster if OPEP countries change their revenue strategies, but most commodities will depend on the Chinese economy. We do know that China is transiting to a more sustainable growth rate of 4-6%. Yet the Chinese government takes all the possible measures to hit their official growth target of 7%. We can suspect there has been a fair amount of negative distortions built-in the Chinese economy to prop up that 7% target, notably in debt levels. Eventually we should expect some hard adjustments. When, where and to what extent these will take place remains mighty hard to predict. But they eventually will. For the time being the economic slowdown in China looms large in the field of oil and commodities, and hence the C$. Sitting out the slum might easily take a couple of years, 3 to 5 if we listen to forecasts from investments banks.

- The profound shift to the digital economy is probably our next biggest challenge to engineer sustainable growth. The shift from a ‘traditional economy with software’ to a ‘digital economy with traditional logistics’ is well under way. But we currently stand in the middle of the pack of followers: not terrible laggards, but neither amongst the drivers of the revolution. This somehow reflects our poor score card on productivity and innovation, an item that has been the subject of countless studies but few deeds in the past 20 years.

So on the whole it does look a little wobbly for the Canadian economy. Then where is the C$ going? Probably down in the short term. You should keep an eye on the 1.50 marker. The C$ will essentially remain much more vulnerable to external factors than domestic ones. Two stand out: The US economy and the China economy. It is the Chinese economy that will remain for us the biggest source of stress . We are happy to see high growth rates in China to sustain commodity prices. But high growth rates also mean that China is moving upmarket fast, from low tech to middle tech to high tech goods. In the mid 1970s Japan overtook the USA in patent applications and it took a mere 5-10 years for Japan Inc to challenge Europe and America in high tech. China is now overtaking the USA in patent applications. Yes we hear that Chinese patent applications are inferior and that China lacks innovation capabilities, but all that was said of the Japanese challenge as well. There is inherently nothing that could prevent China from moving up on the high tech curve. We can be certain high tech challenges are coming up: the writing is now on the wall.

Can we keep up the international pace in high tech and R&D innovation policies? Our track record is lukewarm at best and we are mostly losing ground as a nation in various rankings. As a federal election is now looming, it does not look like that any of 3 main parties has a convincing plan for the economy other than protecting the middle class, and hoping for higher prices for steel, copper and oil.

Brace yourself for a difficult 4-year term in the country.

Andre Du Sault, MPAHarvard

0 Responses

Stay in touch with the conversation, subscribe to the RSS feed for comments on this post.