Owen Sound, 14 April 2016

THERE WILL BE OTHER TRUMPS

The slippery road from inequities to stagnation, from demagogy to decline

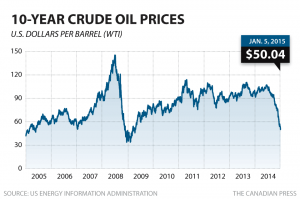

According to the WSJ, real wages in the USA peaked in 1973, before the oil shocks. Sadly for the middle class, they have been on a downhill trend ever since. Past the oil bumps, the decline remained relatively subdued until the 1990s. Economic growth was up, employment felt robust and it was still possible for most workers to do better than the previous generation. But behind the jolly scene however, new forces were building up that would come to change the economic landscape in a dramatic fashion and few people were paying proper attention. These ominous forces of the 1990s were being plastered over by a strong resurgence of consumption in the West, fueled by ever lower prices from China (the Walmart effect) and cheap credit.

For a good while the consumer felt in a sweet spot: decent wages with falling prices for most household goods. But the triple forces of globalisation, technology and financial crises would soon start to whack at the middle class like a tornado set loose in the mid-western plains of America. Skies darkened from 2001 onwards, when China joined the WTO. It took just a few years for the West to realize the fundamental rules of the economic game were being changed for good by both the formidable rise of China and the transformative nature of Internet technology. By 2005 the severity of the shock treatment across most western nations was in plain sight for all to see and sorely feel. Failure to respond to the twin challenges proved systemic across the Western liberal world and was exacerbated by the 2008 financial crisis of our own making. The 1990-2000 years have to be singled out as the true lost decade of the Occidental nations (see previous blog ‘What happened between 1991-201?’ https://sdaconseil.com/?p=341). A systemic failure is an indication that the whole model needs some rethinking, as opposed to fixing a few mere parts.

I recently took on the wheel to revisit Southern Ontario after a similar road trip in 2002: a modest ride of over 2000 km from Windsor to Ottawa. I could not help but observe that most downtown areas of mid-size cities are feeling the brunt of the multiple factory closures: abundant ‘for rent signs’ peppering the Main streets, old paint peeling off, and scores of unemployed and prematurely retired workers nervously sipping their Tim Horton coffee at 10:30 am. It is not just a question of malls built in the outskirts of towns. No, one can feel and hear the pain when talking to shop owners, librarians and other local witnesses of the past 15 years. As a matter of fact the whole Windsor – Gaspé corridor policed by Via Rail, now looks pretty much the same: Rust is spreading where manufacturing was standing. The stakes are now pushed higher: the health of the country.

For Ontario, the future of their auto industry is now at play as new car plant investments are more often than not directed at Mexico. This could essentially leave the famed southern peninsula a mere giant farm plot. In Quebec, the advantage of cheap hydro energy has run its course and cannot protect any more heavy industries such as aluminium. Farming in Quebec is at a disadvantage in terms of colder climate and smaller farm lands. In both provinces, forestry has suffered its own intense clear cuts as newspapers are vanishing. To survive, industries either have to move up in value and quality, or else wages must decline. This is the nature of globalisation: free trade pacts work for the cheapest or the best, not those stuck in the middle. In light of union resistance to lower wages, it is often the plant that ends up closing down. As for innovation as an alternative, it seldom thrives under union terms or bureaucratic guidance. The trickle of jobs flowing down to the Southern states, Mexico or Asia has slowed down, but has not abated. Closures are still part and parcel of media news every single month! After 15 years of shut downs, politicians have run out of easy rhetoric and quick fixes. Fool me once, shame on you, fool me twice, shame on me, angry voters are now thinking.

Thankfully, there are pockets of excellence along the way, mostly hanging around universities, some tech centers such as Waterloo, and cultural icons such as Stratford. But there is a general sense of community values dissolving in this post-industrial age. The young aim for bigger cities in search of opportunities and Toronto, Montreal and Quebec City become the magnets. Urban economies are gradually taking over but our cities are not in best shape. Can services truly prosper without a minimal manufacturing core in the economy?

Precarity is now a word that we often hear in discussion with young university graduates. One morning I kept wandering on the engineering campus of renowned Waterloo University, and I came to estimate the % of students of foreign origin manifestly well above 50%, with a strong representation from China and India. Where were the Canadian engineers? The aftermath of the triple-force tornado has left citizens with a nagging feeling that opportunities that could reliably be counted on 20 years ago, are slipping away for good and that the best days are perhaps gone. All this translates into unexpected political outcomes, with distressed voices finding new trumpets.

We are seeing a greater dispersal of the popular votes covering the full range of the political spectrum, from the far right to the far left, from the Tea Party to the Working Families Party in the USA, from Podemos to the PP in Spain. A whole variety of parties and factions are now playing each other on the fears, emotions and resentment of the shrinking middle class. Language is changing, more radical, more personal and more outrageous. Jeremy Corbin, well anchored in the far left, was unexpectedly elected Labour party leader in the UK, while Marine Le Pen is increasingly brandishing the flag of rightist virtues in France. In Spain the last general election of 2015 has produced no new government despite four months of negotiation. In the American primaries, we are witnessing shifting voting interests, where several center-based mainstream candidates have literally been cast out.

This spreading of votes comes at a cost: it makes it more difficult to build lasting center-based coalitions, good enough to win elections and rule. Instead it has become easier to arrange for micro coalitions to block out new initiatives or reforms proposed by governments. As a result political gridlock has now become a default position. In times of needed changes, meaningful reforms grind to a halt. This is not lost on agile populists and talkers who see openings in these situations and exploit them. They are not shy to pander a ragbag of half-truths, false promises, and disinformation to middle class voters. It just becomes easier to do so to muster a coalition to challenge discredited politicians. While this phenomenon is relatively new in North America, and to some extent in Western Europe, it has been the staple of life in Latin American for a couple of centuries. And there are some reasons to fear the trend at home.

Persistent inequalities in Latin American have a long history of opening doors to Caudillos, the reputed strong men adept at winning the votes at the stump, and then keeping power at all costs with hands of steel covered in velvet. Once in power, they actively work to ring controls around the institutions that count: courts, money systems, homeland security, transport hubs, universities, etc. They usually do this by vetting budgets and nominations by party faithful installed in the targeted institutions. Infiltration is swift, radical and ruthless. Corruption is often the currency that wheels and clinches the changes. Manipulations are just a means to an end. Soon the population is divided between the ‘protected’ by the system, and the ‘unprotected’. The ‘protected’ are usually much adept at accessing benefits, lining their pocket book and even dare pushing for lower taxes.

After a term or two in power, caudillos feel strong enough to move to the more difficult task: Changing the constitution to remove barriers for re-election. They believe they have ‘conquered’ power for good. Witness Peru, Bolivia, and Venezuela in recent years. Even Brazil’s constitution will be hard tested in the current impeachment process of President Dilma. On a recent trip to Nicaragua, there were plenty of warning signs in the media that the Ortega regime was following the standard Chavez playbook in Venezuela: from revolutionist to near dictatorial power. The end result down the road could be predictably frightening in a region known for instability. The traditional safe guards of national constitutions are steadily weakened, removed and replaced. Weak institutions and repeated constitutional changes are the fundamental reasons of the recurring cycles from left to right and from boom to bust in Latin America. That is not about to change. They are somehow caught in a rut.

Although such scenarios look far-fetched in North America, it is the Rob Fords, the Trumps and the Sanders of the current political world who are the first canny operators to tap into the pool of resentment boiling in the middle and lower classes. They are not only gathering support, but they are also showing the way for others to come, and argue. We will therefore see more pandering and more gridlocks from politicians just as the middle class is just as likely to slide further down in the pecking order. There is an existential risk of a nasty cycle of gridlock-decline-gridlock and so on. This has been the fate of past nations. North American middle class people are unused to losing ground. But in the early 1990s I just happened to live in Sao Paulo and estimated the loss of real wages at a whopping 40% in the span of just two years! In the face of repeated financial crises, I saw co-workers selling their cars to buy older ones, selling their houses to buy ones 60 minutes further in the outskirts. Cold hard economic reality always ends up washing out magic and wishful thinking.

It remains today quite unrealistic to envision an opportunistic coalition trying to ram in constitutential changes in the USA or Canada. But we have to remind ourselves that even mayor Bloomberg himself campaigned to change the New York city’s term limit law, and was elected to a third mandate in 2009. Only to be replaced by Bill De Blasio, from the far left. A precedent was set and temptation could not be resisted. Municipal politics in North America are often reminiscent of some practices in Latin America.

In today’s context, the real risk lies rather with extended stretches of bad government, with political parties jockeying for short term tactics and advantages, but never achieving the necessary breakthroughs. Every batch of 10 years of ineffective government will carry a hefty price tag in terms of lost opportunities, weaker institutions, lags in technology, climate burden and drop in competitiveness. In a nutshell, we run the risk of economic stagnation, greater inequities and a resurgence of protectionism. We already are into our 2nd decade of searching for an answer through the mist, and running into circles. This, unfortunately, is how we get on the slippery slope of relative decline. And it is mighty hard to reverse.

André Du Sault, MBA, MPA (Harvard)

Ref: Brookings Institute, WSJ, La Prensa Nicaragua